Why the Education Industry May Be a Hacker’s #1 Target

Most readers of the news are no strangers to the cyberattacks that are plastered on the front pages. Whether it’s the 2017 Equifax breach that turned out to be larger than initially reported or the $534M cryptocurrency heist that Japanese exchange Coincheck suffered earlier in 2018, security breaches are all anyone can talk about these days. But while most of the news cover industries like Finance because of the outright significant value associated with it, many might be surprised to find out that it has a contender in the Education industry.

The Content

While public (and even some private) school systems may not be holding onto a large sum of money in a vault or in the form of any kind of currency (fiat or crypto), educational institutions are often targeted by hackers for the research that they produce. In April 2017, the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU) were attacked in a carefully-planned attempt to take classified government research data. While thankfully, no data was taken, the hacker had been lurking undetected in the systems for quite some time.

These hacks are hypothesized to be from nation-states, most likely because universities often work in conjunction with the government in order to do research regarding political military strategies or technology associated with energy or military involvement. More and more universities are finding themselves unprepared to deal with cyberthreats and, in March 2016, it was found that more than 30% of UK universities suffer cyberattacks every hour.

The Data

Your first thought when you think of hackers looking for data would be things like social security numbers or credit card numbers, but did you know some of the hottest items on the Dark Web are student email addresses?

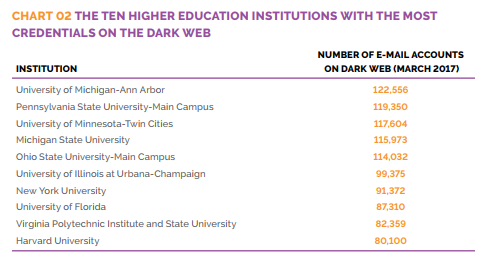

In March 2017, the Digital Citizens Alliance (DCA) released their findings about criminals stealing and utilizing college credentials. As of 2017, there are nearly 14 million email accounts on the Dark Web, being sold from $3.50 to $10. Although larger universities obviously have a larger number of accounts that may be breached, smaller universities are also making their way up the ranks.

Why are these email addresses such a valuable commodity when there are billions of other email addresses available on the Web? A common suffix at the end of email addresses generated by US-based colleges or universities, the “.edu” address can bring about perks that other addresses cannot. For example, expensive software and other products can come at a sharp discount for those in academia. Certain online retailers also offer free expedited shipping for students or teachers, which some may deem worth the few bucks.

Aside from getting free Amazon Prime, what might be a motive in getting a “.edu” address? Hackers may also attempt to use them for phishing or getting access to more sensitive data that an educational institute holds. For example, a hacker may attempt to login with stolen credentials in order to access more information about wealthy donors or available grants.

The Network

As we’ve seen so far, while there are instances when hackers attempt to hack into university systems for an email address or for snatching up research, many times they utilize these hacks as a gateway into something much bigger. Universities, especially large or prestigious ones, have a vast network of computing systems, and these infrastructures can be used to launch even bigger attacks through phishing or injecting malicious code into websites that the faculty or students frequently utilize.

Although the financial sector may take over the front pages when it comes to cyberattacks, education is also a popular target for hackers, and we hope you can now see why. With so many compromised emails already, universities and schools may have to rethink their security strategies. Their security architecture may not necessarily be lacking (though there may still be institutions that have not implemented basic encryption and a WAF in order to protect their data and applications) as many of the breaches don’t occur within the university’s system in itself, but from other websites and platforms that faculty and students regularly visit.

So why does this matter?

It is always easy to underestimate the value of a target for hacking. But the creative uses for data will only keep growing the more digitally connected we are in the pursuit of greater convenience, value and innovation. However, the stakes tend to differ between the individuals and the organizations they’re a part of. While students may not see the harm of having their university or school email addresses stolen and misused, and bypass how critical their roles are in securing the wider university network, suffering a breach could mean botched collaborative research opportunities with high-value partners for the institution.

In countries like the United States, cybersecurity education has been increasingly placed at the core of the curriculum, but it may need to be taken one step further. There has been discussion about the parallels between managing public health and cyber “hygiene,” by treating cybersecurity as a public good. Perhaps if students and universities can view their connected networks in the same light, strides could be made in raising overall resilience against cyberattacks in the industry.